Life In A Medieval Castle

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Medieval Gardens

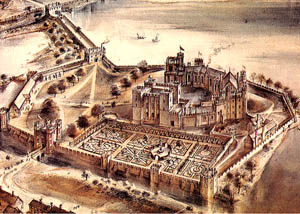

Medieval Castles, and to an even greater extent Monasteries, carried on an ancient tradition of garden design and intense horticultural techniques in Europe. Gardens were funcional and included kitchen gardens, infirmary gardens, cemetery orchards, cloister garths and vineyards. Vegetable and herb gardens helped provide both alimentary and medicinal crops, which could be used to feed or treat the sick. Gardens were laid out in rectangular plots, with narrow paths between them to facilitate collection of yields. Often these beds were surrounded with wattle fencing to prevent animals from entry. Monasteries might also have had a "green court," a plot of grass and trees where horses could graze, as well as a cellarer's garden or private gardens for obedientiaries, monks who held specific posts within the monastery. In the kitchen gardens, fennel, cabbage, onion, garlic, leeks, radishes, and parnips might be grown, as well as peas, lentils and beans if space allowed for them. Infirmary gardens could contain savory, costmary, fenugreek, rosemary, peppermint, rue, iris, sage, bergamot, mint, lovage, fennel and cumin, amongst other herbs. A herber was a herb garden and pleasure garden. A Hortus Conclusus was an enclosed garden representing areligious allegory). A Pleasaunce was a large complex pleasure garden or park. The word paradise comes from a Persion word for a walled garden. The term was used by St. Gall to refer to an open court in monastery garden, where flowers to decorate the church were grown. In the later Middle Ages, texts, art and literary works provide a picture of developments in garden design. Pietro Crescenzi, a Bolognese lawyer, wrote twelve volumes on the practical aspects of farming in the 13th century and they offer a description of medieval gardening practices. From his text we know that gardens were surrounded with stonewalls, thick hedging or fencing and incorporated trellises and arbors. They borrowed their form from the square or rectangular shape of the cloister and included square planting beds. Grass was also first noted in the medieval garden. In the De Vegetabilibus of Albertus Magnus written around 1260, instructions are given for planting grass plots. Raised banks covered in turf called "Turf Seats" were constructed to provide seating in the garden. Fruit trees were prevalent and often grafted to produce new varieties of fruit. Gardens included a raised mound or mount to serve as a stage for viewing and planting beds were customarily elevated on raised platforms. Medieval and particularly Renaissance gardening was heavily influenced by the writings of the ancient Greeks and Romans, notably Columella (On Agriculture), Varro (On Agriculture: Rerum rusticarum), Cato (On Agriculture: De re rustica), Palladius (On Husbandry), Pliny the Elder, Dioscorides Pedanius, of Anazarbos.(De Materia Medica) While there isn't a clear delineation between gardens for pleasure and utilitarian gardens, orchards, etc. it's clear that some parts of some gardens were intended primarily to be a delight to the senses, and others for their end products.

Most every manor, abbey, and great estate would have utilitarian gardens, demesne farm fields, and perhaps woods and even vineyards or orchards in addition to some sort of pleasure garden. One of the primary characteristics of the medieval garden was that, large or small, it was always enclosed by pole fences, hedges, banks and ditches, Stone, Brick , Wattle (a sort of basket work of willow withies, osiers, etc. woven around stakes in the ground.) Albertus Magnus was a great admirer of lawns: "For the sight is in now way so pleasantly refreshed as by fine and close grass kept short." Most writers recommend digging out the original 'waste' plants, killing the seeds in the soil by flooding with boiling water, then laying out the lawn with turves laid in and pounded well. Another writer recommends mowing them twice a year; lawnmowing would have been done with scythes or primitive shears. Beds could be raised or sunken:

Sunken beds appear to be used primarily in Islamic gardens, where the idea would be to facilitate irrigation and keep the earth from drying out. Good examples appear in the Alhambra in Spain. (Islamic gardens tended to strongly follow the Roman pattern of square layouts and canals or streams running through the garden.) Grapes, roses and rosemary in particular were grown over trellises; gilliflowers (carnations, pinks) were trellised in their pots to keep them from falling over. Other kinds of vines were also grown that way. Lattices with climbing plants and trellises with climbing plants were used as garden walls, often starting from the back of a turfed bed or seat, and also for arches and pergolas. Topiary animals appear in late period, either self topiary, or fastened over a frame, as in this account of Hampton Court in 1599:

Trees were planted either along walls, geometrically placed in orchards (about 20 feet apart), or pleached into allees. Some trees, such as the walnut, were avoided in gardens, but fruit trees and other trees with a good smell or pleasant aspect were included in most gardens as well as adjoining orchards. Sometimes trees were trained against a wall but that may be a late period development. There are two techniques used in forestry that are worth mentioning: pollarding and coppicing. Both were and are used to get the maximum growth of branches and wood out of farmed trees, so they wouldn't have been used much in gardens, except possibly in hedging. Coppiced trees, such as beeches, were cut down at ground level or a little above, and the stumps allowed to sprout suckers. After the suckers had grown to medium sized branches-- or the right size for fences, wattle, poles, etc-- they were harvested. Pollarding is the same process, but done much higher off the ground, beyond nibbling reach for deer, cattle, etc. Pollarding survives as a landscaping technique and as the result of trees being cut back for electric and telephone lines. There is evidence in the pictoral representations of plants in pots either outdoors or in the house. Gillyflowers in pots appear to have been especially popular in that period, both indoors and out. Potted plants and trees are depicted placed on top of grassy beds in gardens and entryways-- these may have been tender perennials or fruit trees. Pots made of ceramic seem to have been the norm, usually in the familar 'Italian' flowerpot style, or in the shape of urns, with either wide tops or narrow. Plants are also pictured growing from wide-mouthed jugs or crocks. Woven baskets are shown being used to transport plants from one place to another. Potting plants were used to extend the season, as well. Thomas Hill points out that you can start your cucumbers early if you plant them out in pots, leaving them out all day in warm weather and moving them into a warm shed at night.

Tender perennials and Mediterranean trees such as the orange, bay and pomegranate were sometimes managed this way in Northern Europe during the Renaissance, raised in tubs and brought into a shed, sometimes a heated shed, in the winter. Le Menagier says to bring violets inside in pots for the winter. Not used in every garden, but in vegetable and medicinal gardens, raised beds were often a major feature from the plan of St. Gall onward. Columella, a Roman writer, dictated:

Landsberg suggests:

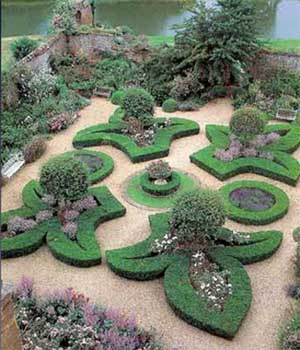

Parkinson suggests that beds be edged with lead "cut to the breadth of foure fingers, bowing the lower edge a little outward," or "oaken inch boards four or five inches broad," or shank bones of sheep, or tiles, or "round whitish or blewish pebble stones of some reasonable proportion and bignesse." He says, with distaste, that jawbones were sometimes used as edgings in the Low Countries. In any case, beds were almost universally rectangular, and arranged in aregular pattern, either windowpane check or checkerboard. The fashion of putting a central circular feature with semi-rectangular beds with their corners cut out appears, according to Roy Strong, to have been introduced after 1600. Turfed seats were a major feature of 'gardens of pleasure'. Marble or stone seats also appear. One illustration shows a portable wooden bench. Turfed seats, also called excedra, were generally built along the lines of slightly higher raised beds, the outer wals constructed with wood planks, bricks or wattles, though some illustrations show the benches with sod sides as well. Often turfed seats were arranged around the inner borders of an enclosed 'herber', providing seats as well as anchorage for the trellised plants Tables also appear, as in one illustration of the Garden of Paradise, where the Virgin has at her elbow a marble table containing a glass of something to drink and some snacks. Dining al fresco was a popular summer activity, and there are many illustrations of couples and groups eating, drinking, and/or playing games at tables and benches set up in the garden. Markham's English Husbandman is very emphatic about the need for a water source in a garden. The 14-16th century gardens we have depictions of generally include a water feature. They were generally surrounded by a lawn, rather than a planting of any sort. Springs were popular, often opening into a square pool or trough from which water could be drawn or washing done. Springheads and streams could supply pools for drinking from, washing in, or even keeping fish in. Though the most popular presentation of outside bathing is Bathsheba, other illustrations show outside bathing in houses of ill repute also. Big ornate fountains with statuary became popular in the Renaissance. Fountains were powered by hydraulics, either water from a springhead or stream, or water piped in via aqueduct. A stream might run through or around a garden (like a moat) or the runoff from a fountain or to a fountain could be made into an artificial stream or water-stairs. (The Italian villa gardens would detour an entire stream to run downhill through the property and power its fountains.) Naomi Miller, in her article "Medieval Garden Fountains" in Medieval Gardens, Dumbarton Oaks, 1986, describes the typical fountain before the vogue for classical statuary beginning in the 14th century:

Statuary does not appear to have been a major part of early medieval gardens, except in the cases of fountains, and in abbeys, elaborate fountain-type handwashing arrangements. In the Renaissance, interest in statuary, specifically Greek and Roman statuary, boomed. From "museum" gardens designed to display and highlight one's collection of Greek and Roman statues (or copies thereof), the idea of statues as focal points for gardens and grottos took hold. Generally, statues were in the form of people (Greek, Roman, or Christian characters), mythical animals, or birds, horses, and occasional putti (cherubim types), medusas, or heraldic beasts on the walls seem to be typical. River gods, water nymphs, goddesses with or without fountain outlets in their bosoms, children pouring water from jars, muses, mountain giants, were all popular as statuary and fountains in the last part of the 16th century. Many major English gardens from the Elizabethan period had references to Elizabeth as Diana or Cybele, or as the Rose. Hampton Court, one of Henry VIII of England's principal seats, was enlivened by sundials and "The Kinges bestes made to be sett vp in the privie orchard . . . vij of the Kinges Bestes. That is to say ij dragons, ij greyhounds, i lyon, i horse and i Antylope . . ." (1531 household accounts, quoted by R. Strong). This fashion of having heraldic beasts carved out of wood and set up on poles in your garden seems to have spread somewhat, as the beasts appear in other places; there were also topiary beasts appearing in gardens of the period. These beasts might be painted in heraldic colors or gilded, either on appropriate parts or all over. Eating out of doors in summer was apparently quite popular; special banqueting houses were created. Some were very odd, such as the 'Mouth of Hell' cavern in an Italian Renaissance garden, and another one constructed on a platform built on the branches of an enormous linden tree. No major landowners pleasure park was complete without one. Artificial caves cut into a hillside, or in a walled building, generally with fountains, hydraulic toys, statuary, carvings and/or paintings were the mode at the very end of period, a trend that continued into the seventeenth and 18th centuries. Labyrinths, in which one cannot get lost, seem to have been more popular in period than Mazes. Copying the fashion in Roman tiles (and perhaps a Roman boys' exercise), big festival or game labyrinths were made of cut turf in some places; by the sixteenth century, the inclusion of a labyrinth laid out with herbs and small shrubs seems to have been one way to use up space in a big garden. "Hyssop, thyme, and cotton lavender, which were used in the early mazes, are small-- the grow, at the most, knee-high. Mazes made with these are therefore to be surveyed as well as walked in. Their color should be remembered, with box and yew also recommended: these were invaluable as evergreens. . Charles Estienne in his Agriculture et Maison Rustique recommends. . . 'and one bed of camomile to make seats and labyrinths, which they call Daedalus.' In the first English version of this work, translated by Richard Surflet in 1600. . .'these sweet herbes . . . some of them upon seats, and others in mazes made for the pleasing and recreating of the sight.'" Thacker, The History of Gardens. Knotwork and Parterres (Embroidery-work) apparently began to be fashionable in the early 1500's, though its heyday was in the 1600's. Knots or pattern-work laid out in plants and/or colored stones, usually in blocks of four -- at first generally mirrored both horizontally and vertically, then, later, mirrored only along one axis and even only broken into 2. Markham gives instructions for laying out your knots. (Some knots included spots for the inclusion of the owner's heraldry, etc.) In 1599, a observer's account of some partierres at Hampton Court (quoted by R. Strong, p. 33):

Elaborate, embroidery work 'partierres" were a feature of gardens in the late 1600s and early 1700s. Major manor gardens of the latter part of the 16th century often sited the gardens so that they could be seen from the owner's principal private quarters; royalty might have two gardens, one for the king and one for the queen. Hugh Platt, in Floraes Paradise (1608) advocated what Campbell (Charleston Kedding) calls "Sun-entrapping fruit walls, concave, niched, or alcoved . . . He suggesed lining concave walls with lead or tin plates, or pieces of glas, which would reflect the sun's heat back onto the fruit trees. He also considered warming the walls with the backs of kitchen chimneys." Campbell also gives a good description of period references to hotbeds in Moorish agricultural manuals, in De Crescenzi, and in Thomas Hill. These hot beds were constructed by putting fresh dung in a pit and either putting soil over it and planting in the soil, covering over the plants with a shelter in inclement weather. Peasants had mostly just a vegetable garden, perhaps with some medicinal herbs, surrounded by a wattle fence to keep the pigs, etc. out. Definitely they grew pease, beans, etc.

Monasteries would have multiple gardens: vegetable gardens, an Infirmarer's garden of medicinal herbs, cloisters or orchards for pacing and praying, and perhaps herbers also. Monasteries, hermitages and almoner's establishments sometimes had separate plots for each person to work. Description of the grounds of the Cistercian Abbey of Clairvaux in the 12th century:

Carole Rawcliffe, in an article on Hospital Nurses and their Work, notes that hospitals and infirmaries had gardens that not only had practical function but also "contributed in less immediately obvious ways to the holistic therapy characteristic of the time." She goes on:

Castles and manors often had gardens of pleasure for walking in, with seats, private nooks screened from the wind for sitting, flowery meads for sitting and/or playing games. We see many of these in pictures of young ladies and pictures of the Virgin and Child. Italian Renaissance gardens are characterized by lots of space, walks, statuary and 'toys'. The fashion for god and goddess statues, statues with water coming from significant points, and sculptures meant to indicate river gods, naiads, dryads, etc. was extreme; they also attempted to spotlight (or create, if necessary) Etruscan ruins on the property. From The Decameron (Bocaccio, mid-14th century):

Parks often included multiple structures, many water features, and, at least according to Crescenzi, were stocked with wild beasts. The large gardens at Woodstock, perhaps orginally made for Henry II's light'o'love Rosamund, and suspected by at least one author to have been made imitation of those in the romance of Tristan and Iseult, are an example.

The park at Hesdin, northern France, created in 1288, included:

Compare this prescription from Crescenzi:

Orchard trees that give fruit (apples, pears, plums); tender perennials such as bay, orange, pomegranate in the south and later in period, Olives and date palms in the south. Nut trees such as chestnut and almond. Pine and Cypress. Of non-fruiting trees, linden or lime trees were popular in northern Europe; William Stephen in 1180 mentions elms, oaks, ash, and willow "along watercourses and to make shady walks" (says Hobhouse); the Roman de la Rose also mentions fir, and oriental plane trees. Crescenzi says:

He also suggests box, broom, cypress, dogwood, laburnum, rosemary, eonymous or spindle and tamarisk. Albertus Magnus recommended:

He also suggested a lawn, a bench of flowering turf, seats in the center of the garden, and a fountain. A collected Albertus Magnus quote (John Harvey's translation):

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

More on Life in a Medieval Castle

Introduction to Life in a Medieval Castle

Officers & Servants in a Medieval Castle

Mills: Windmills and Water Mills

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

| :::: Link to us :::: Castle and Manor Houses Resources ::: © C&MH 2010-2014 ::: contact@castlesandmanorhouses.com ::: Advertising ::: |