Life In A Medieval Castle

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

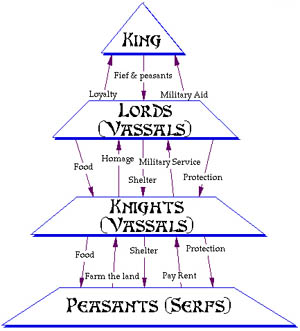

The Feudal System

Under the feudal system all land in a kingdom belonged to the king. He parcelled out large chunks to great Lords ("Tennants-in-Chief") in exchange for their military and political support. They parcelled out smaller parcels to lesser lords ("Mesne Tenants") on similar terms. They in turn parcelled out smaller parcels to local lords, who did the same to the peasantry. Thus was formed a hierarchical network below the king of earls, barons, lords of the manor and villains, all bound together by pairs of reciprocal obligations. The lowest operational unit in this system was the manor, controlled by a lord typically holding the rank of a knight. He lived in a manor house and controlled a large area of land along with its workers. In principal the manorial system and the feudal system are to different things but in Medieval Europe they were closely linked. The system of manorial land tenure was conceived in Western Europe, initially in France but exported to areas affected by Norman expansion during the Middle Ages, for example the Kingdoms of Sicily, Scotland, Jerusalem, and England. The system had its own vocabulary. The junior party in a feudal arrangement arrangement was known as a vassal. A vassal or liege held land (a "fief") from a lord to whom he paid homage and swore fealty. A vassal was not therefor necessarily a minor figure: everyone in the feudal system below the king was a vassal, even the greatest lords in the land. King William the Conqueror used feudalism to reward his Norman supporters for their help in the conquest of England. The land belonging to Anglo-Saxon earls was taken and given to Norman Knights and Nobles, split into Manors. The Medieval Feudal System ensured that everyone owed allegiance to the King and their immediate superior. Everyone was expected to pay for the land by providing certain services in the form of man-days of work. This work could be for farming or military service or both. Military service took the form of so many fighting men (knights, archers, pikemen, etc for so many days per year, including clothing and weapons. Not all manors were held necessarily by lay lords rendering military service (or cash in lieu) to their superior. A substantial number of manors (estimated by value at 17% in England in 1086) belonged directly to the king. An even greater proportion (in most European states a third to a half) were held by bishops and abbots. Ecclesiastical manors tended to be larger, with a greater villein area than neighbouring lay manors. Medieval manors varied in size but were typically small holdings of between 1200 - 1800 acres. Every noble had at least one manor; great nobles might have several manors, usually scattered throughout the country; and even the king depended on his many manors for the food supply of the court. England, during the period following the Norman Conquest, contained more than nine thousand of these manorial estates. The lord's land was called his "demesne," or domain which he required to support himself and his retinue. The rest of the land of the Manors were allotted to his tenants. A peasant, instead of having his land in one compact mass, had it split up into a large number of small strips (usually about half an acre each) scattered over the manor, and separated, not by fences or hedges, but by banks of unploughed turf. Besides his holding of farm land each peasant had certain rights over the non-arable land of the manors - the common land. A peasant could cut a limited amount of hay from the meadow. He could turn so many farm animals including cattle, geese and swine on the waste. He also enjoyed the privilege of taking so much wood from the forest for fuel and building purposes. A peasant's holding, which also included a house in the village, thus formed a self-sufficient unit. The labour required of villains was called corvée. Work was usually intermittent; typically only a certain number of days' or months' work is required each year. The system differed from chattel slavery in that the worker was not owned outright – being free in various respects other than in the dispensation of his or her labour. In time corvée came to resemble a tax or tribute, as it suited all parties to replace the work by an amount of money or crops or other goods. The Feudal System included a complex system of rights and obligations. The right to hunt was highly valued by nobles. The severest and cruellest penalties were imposed on "villains" who killed game on the lands owned by a lord. The Manor House was residential property, and differed from castles in that it was not built for the purpose of attack or defence. The Manor House varied in size, according to the wealth of the lord but generally consisted of a great hall, solar, kitchen, storerooms and servants' quarters.

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Lords of Medieval Manors exercised

certain rights including Hunting and Judicial rights. The Lord of

the Manor was based in the Manor House and from here he conducted

the business of the manor. People who worked on the manor included:

As common-law practice protected the rights of the villein, tenancy at the pleasure of the lord gradually developed into the added security of copyhold leases. A portion of the demesne lands, called the lord's waste, served as public roads and common pasture land for the lord and his tenants. Since the demesne surrounded the principal seat of the lord, it came to be loosely used of any proprietary territory: "the works of Shakespeare are this scholar's demesne." The term feudalism and the system it describes were not conceived of as a formal political system by the people living in the Medieval Period. The term was coined in the early modern period (17th century). Three primary elements characterised feudalism: lords, vassals, and fiefs Before a lord could grant land (a fief) to someone, he had to make that person a vassal. This was done at a formal and symbolic ceremony called a commendation ceremony composed of the two-part act of homage and oath of fealty. During homage, the lord and vassal entered a contract in which the vassal promised to fight for the lord at his command. Once the commendation was complete, the lord and vassal were in a feudal relationship with obligations to one another. The vassal's principal obligation to the lord was "aid", or military service. Using whatever equipment the vassal could obtain by virtue of the revenues from the fief, the vassal was responsible to answer to calls to military service on behalf of the lord. Security of military help was the primary reason the lord entered into the feudal relationship. In addition, the vassal sometimes had to fulfil other obligations to the lord. One of those obligations was to provide the lord with "counsel", so that if the lord faced a major decision, such as whether or not to go to war, he would summon all his vassals and hold a council. The vassal may have been required to yield a certain amount of his farm's output to his lord. Land-holding relationships of feudalism revolved around the fief. Depending on the power of the granting lord, grants could range in size from a small farm to a great lordship. The system encompassed almost the whole of society. At the lowest level working men held land from the local Lord of the Manor, He held his lands from a Baron, who held his from a Earl, who in turn held his from the King. A network of rights and obligations held everyone in a place on a strict hierarchy appointed for them by God - as the Church then taught. The lord-vassal relationship was not restricted to members of the laity; bishops and abbots, for example, were also capable of acting as lords. Indeed somewhere between a third and a half of all revenues of Christian Europe were channelled into Church coffers for centuries largely through bishops and abbots in their capacity as feudal lords. For a while during and after the reign of Pope Innocent III, the papacy claimed to sit at the apex of a single Christian feudal hierarchy: below them as feudal tenants and owing them fealty were all Christian emperors and kings. The Pope himself held the whole world in fief from God himself. The involvement of the Church in the feudal system is remembered in a vestigial act of homage build into Christian prayer. When a vassal swore fealty to his lord he held his hands together and his lord placed his hands around them. Before the feudal period Christians had prayed with their arms held out with open palms. Now they prayed with hands together as in an act of homage to God, inviting him to place his hands around theirs. At the height of witch mania, witches were often imagined to pay homage to Satan. This strong attachment between the Church and the feudal system explains why the Church was so opposed for so long to alternative systems of government such as democracy - condemned throughout the nineteenth century as satanic. The oath known as "fealty" implied lesser obligations than did "homage". One could swear "fealty" to many different overlords with respect to different land holdings, but "homage" could only be performed to a single liege, as one could not be "his man", i.e. committed to military service, to more than one "liege lord". There have been conflicts about obligations of homage. The Angevin monarchs of England were sovereign in England, so had no duty of homage regarding those holdings; but they were not sovereign regarding their French holdings. So Henry II was King of England, but also Duke of Aquitaine and Normandy and Count of Anjou. The Capetian Kings, though weak militarily, claimed a right of homage for these dukedoms and county. The usual oath was therefore modified by Henry to add the qualification "for the lands I hold overseas." The significance was that no "knights service" was owed for his English lands. After King John was forced to surrender Normandy to the France King in 1204, English magnates with holdings on both sides of the Channel were faced with conflict. John still expected to recover his ancestral lands, and those English lords who held lands in Normandy had to choose sides. Many were forced to abandon their continental holdings. Two of the most powerful magnates, Robert de Beaumont, 4th Earl of Leicester and William Marshal, Earl of Pembroke, negotiated an arrangement with the French king that if John had not recovered Normandy in a year-and-a-day, they would do homage to Philip. The conflict between the French monarchs and the Angevin Kings of England continued through the 13th century. When Edward I was asked to provide military service to Philip III in his war with Aragon in 1285, Edward made preparations to provide service from Gascony (but not England - he owed no service to France for the English lands). Edward's Gascon subjects did not want to go war with their neighbours on behalf of France, and they appealed to Edward that as a sovereign, he owed the French King no service at all. A truce was arranged before Edward had to decide what to do. But when Phillip III died, and his son Philip IV ascended the French throne in 1286, Edward performed "homage". In doing so Edward added yet another qualification - that the duty owed was "according to the terms of the peace made between our ancestors"

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

|

More on Life in a Medieval Castle

Introduction to Life in a Medieval Castle

Officers & Servants in a Medieval Castle

Mills: Windmills and Water Mills

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Charter of Homage and Fealty, 12th Century

The following is a translation into English of Charter of Homage and Fealty dated 1110, between Bernard Atton, Viscount of Carcassonne and Leo, Abbot of the Monastery of St. Mary of Grasse [modern Lagrasse in the Corbieres].

From Teulet: Layetters du Tresor des Chartres No. 39, Vol 1., p. 36, translated by E.P. Cheyney in University of Pennsylvania Translations and Reprints, (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1898), Vol 4:, no, 3, pp. 18-20. http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/source/atton1.html

More on Minerve More on Termes |

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

| :::: Link to us :::: Castle and Manor Houses Resources ::: © C&MH 2010-2014 ::: contact@castlesandmanorhouses.com ::: Advertising ::: |