|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Walls

Other than simple towers, all castles have surrounding defensive

walls.

as the Romans knew, simple walls can be difficult to defend because

the defenders need to be able to fire upon all areas outside but

near the walls. The Roman solution was to construct towers at intervals

along the walls. These towers provided covering fire for the walls.

This same solution was used in Medieval times.

Medieval builders used a number of techniques to strengthen walls,

for example building them thicker at the base to prevent undermining

(taluses), and cutting the stones in such a way as to be able to

withstand high impact projectiles (bossing).

Castle walls were also used to help defences in other ways - for

example walkways on top of the walls (chemins de rondes) allowed

defenders to move quickly around the castle defences. Battlements

(crenellations) protected them for enemy fire. Simple battlements

could support further defences such as hourdes in times of trouble,

later to be replaced by permanent stone machicolations.

Walls were often provided with arrow loops and later by gun ports

(cannoniers) to enable defenders to fire on the enemy in relative

safety.

|

The curtain walls at the Chateau Comtal with

wooden Hourds, inside the Cité of Carcassonne

|

|

|

|

The Inner curtain walls at Carcassonne

|

|

| |

|

Not only castle needed protection. In areas

where the Church was particularly unpopular its buildings

were often build like castles. This is the Cathedral at Albi

in France.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Curtain Walls (Courtines)

A curtain wall or courtine is a type of defensive wall forming

part of the defences of medieval castles and towns.

The curtain wall surrounded and protected the interior courtyard,

or bailey, of a castle. These walls were often connected by a series

of towers or mural towers to add strength and provide for better

defense of the ground outside the castle, and were connected like

a curtain draped between these posts.

Additional provisions and buildings were often enclosed by such

a construction, designed to help a garrison last longer during a

siege by enemy forces.

With the introduction of star forts (trace italienne fortification)

the height of the curtain walls was reduced and additional outworks

such as ravelins and tenailles were added beyond the ditch to protect

the curtain walls from direct cannonading.

|

|

|

|

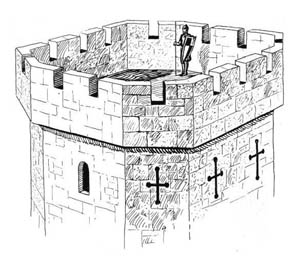

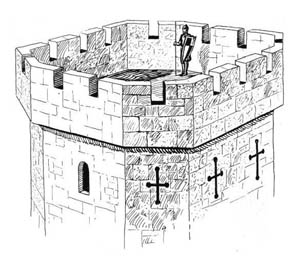

Battlements & Crenellations

Castle

walls were often crenelated, that is to say provided with projections

called merlons. These merlons provided protection for defenders

while allowing them to shoot from the gaps between. Some merlons

were provided with their own arrow slits, providing the defenders

with even more protection (as shown near right) Castle

walls were often crenelated, that is to say provided with projections

called merlons. These merlons provided protection for defenders

while allowing them to shoot from the gaps between. Some merlons

were provided with their own arrow slits, providing the defenders

with even more protection (as shown near right)

A battlement (also called a crenellation) in defensive architecture

such as that of city walls or castles, comprises wall) in which

portions have been cut out at intervals to allow the discharge of

arrows or other missiles. These cut-out portions form crenels (also

known as carnels, embrasures, loops or wheelers).

The solid widths between the crenels are called merlons (or cops

or kneelers). A wall with battlements is said to be crenelated or

embattled. Battlements may have protected walkways (chemin de ronde)

behind them.

The term originated around the 14th century from the Old French

word batailler, "to fortify with batailles" (fixed or

movable turrets of defence).

Battlements have been used for thousands of years; the earliest

known example is in the palace at Medinet-Abu at Thebes in Egypt,

which allegedly derives from Syrian fortresses. Battlements were

used in the walls surrounding Assyrian towns, as shown on bass reliefs

from Nimrud and elsewhere. Traces of them remain at Mycenae in Greece,

and some ancient Greek vases suggest the existence of battlement.

Battlements can be seen in the Great Wall of China.

Romans used low wooden pinnacles for their first aggeres (terreplains).

In the battlements of Pompeii, additional protection derived from

small internal buttresses or spur walls against which the defender

might place himself so as to gain complete protection on one side.

In the battlements of the Middle Ages the crenel comprised one-third

of the width of the merlon: the latter, in addition, could be provided

with arrow-loops of various shapes, depending from the weapon to

fire. Late merlons permitted fire from the first firearms.

From the 13th century the merlons could be connected with wooden

shutters that provided added protection when closed. The shutters

were designed to be opened temporarily to allow fire against attackers,

and closed during reloading.

The term embrasure, in military architecture, refers to the opening

in a crenellation or battlement between the two raised solid portions

or merlons, sometimes called a crenel or crenelle. The purpose of

embrasures is to allow weapons to be fired out from the fortification

while the firer remains under cover. The splay of the wall on the

inside provides room for the soldier and his equipment, and allows

them to get as close to the wall face and arrow slit itself as possible

(see right). Excellent examples of deep embrasures with arrow slits

are to be seen at Aigues-Mortes and Château de Coucy, both

in France.

By the 19th century, a distinction was made between embrasures

being used for cannon, and loopholes being used for musketry. In

both cases, the opening was normally made wider on the inside of

the wall than the outside. The outside was made as narrow as possible

(slightly wider than the muzzle of the weapon intended to use it)

so as to afford the most difficult possible shot to attackers returning

fire, but the inside had to be wider in order to enable the weapon

to be swiveled around so as to aim over a reasonably large arc.

A distinction was made between vertical and horizontal embrasures

or loopholes, depending on the orientation of the slit formed in

the outside wall. Vertical loopholes—which are much more common—allow

the weapon to be easily raised and lowered in elevation so as to

cover a variety of ranges easily. To sweep from side to side the

weapon (and its firer or crew) must bodily move from side to side

pivoting around the muzzle, which is effectively fixed by the slit.

Horizontal loopholes, on the other hand, facilitate quick sweeping

across the arc in front, but make large adjustments in elevation

very difficult. They were usually used in circumstances where the

range was very restricted anyway, or where rapid cover of a wide

field of arc was preferred.

Another

variation had both horizontal and vertical slits arranged in the

form of a cross, and was called a crosslet loop or an arbalestina

since it was principally intended for arbalestiers (crossbowmen).

In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, after the crossbow had

become obsolete as a military weapon, crosslet loopholes were still

sometimes created as a decorative architectural feature with a Christian

symbolism. Another

variation had both horizontal and vertical slits arranged in the

form of a cross, and was called a crosslet loop or an arbalestina

since it was principally intended for arbalestiers (crossbowmen).

In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, after the crossbow had

become obsolete as a military weapon, crosslet loopholes were still

sometimes created as a decorative architectural feature with a Christian

symbolism.

|

| |

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

| Embassure at Caen |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

Bossing

Bossed stones are cut building stones which are left rough on the

external side.

Historians used to debate why builders did this. One theory was

that it saved money since there was less finishing for the stone

mason. Another was that it gave an impression of strength.

Now we know. According to several texts on catapults, bossing was

a means of strengthening a wall against heavy shot. The projection

dispersed the energy of the stone shot and prevented a direct energy

transfer to the wall. Its use pre-dates Rome.

After the development of firearms, builders switched to other materials,

such as brick, which absorb even greater impacts.

The technique is similar to the modern use of spaced armour on

tanks

|

| Bossing around an arrow slit

at Carcassonne |

|

|

|

|

Batters or Taluses or Plinths

|

|

A batter or talus is a sloping face at the base of a fortified

wall.

Defensive walls were often built thicker at the bottom. This

made it more difficult for attackers in three ways.

First, attackers would have a more diffult job in breaking

through or undermining the wall because of its great mass.

Second, conventional siege equipment is less effective against

a wall with a talus. Scaling ladders may be unable to reach

the top of the walls and are also more easily broken due to

the stresses caused by the angle they are forced to adopt.

attackers would have greater difficulty in moving siege engines

up against a talused wall - to reach the top of the wall they

required not only height but a substantial overhang. Siege

towers cannot approach closer than the base of the talus,

and their gangplank may be unable to cover the horizontal

span of the talus, rendering them useless.

|

|

Third, defenders are able to drop rocks over the walls, which will

shatter on the talus, spraying a hail of shrapnel into any attackers

massed at the base of the wall.

The talus is feature of some late medieval castles, especially

prevalent in crusader constructions. There is a spectacular talus

at Krak - shown here on the right.

|

| Talus at Carcassonn |

|

| |

| A massive talus at Krak des Chevaliers |

|

| |

| |

|

|

Coca, Segovia, Castile-Leon, Spain

with impressive taluses

|

|

|

|

Castel Nuovo (or Maschio Angioino), Piazza

Castello, Naples, Italy with spectacular batters (or taluses)

on the round corner towers

|

|

|

|

Palacio de la Aljafería (The Aljafería

Palace), Zaragoza, Spain with a spectacular talus / bastion.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Chemins de Rondes

A chemin

de ronde (French, "round path" or "patrol path") is

a raised protected walkway behind a castle battlement. A chemin

de ronde (French, "round path" or "patrol path") is

a raised protected walkway behind a castle battlement.

In early fortifications, high castle walls were difficult to defend

from the ground. The chemin de ronde was devised

as a walkway allowing defenders to patrol the tops of ramparts,

protected from the outside by the battlements or a parapet,

placing them in an advantageous position for shooting or dropping

projectiles.

|

|

|

|

Hourdes

|

Hourds are defensive wooden structures built onto the top

of a defensive wall. They would then be covered in the wetted

skins of freshly slaughtered animals to minimise the risk

of attackers being able to set fire to them.

Hourdes could be assembled when trouble threatened - in times

of peace they were not needed.

Walls built to bear hourdes have a characteristic row of

double holes ready to take the supporting wooden beams.

|

|

|

Hourds have been reconstructed on the Chateau Comptal at Carcassonne

as shown on the right

|

The purpose of a hoarding was to allow the defenders to improve

their field of fire along the length of a wall and, directly

downwards to the wall base. They were wooden structures build

on the top of walls. Like all defensive wooden structures

they were covered in fresh animal skins to keep them fireproof.

In peacetime, hoardings could be stored as prefabricated

elements. In some castles, construction of hoardings was facilitated

by putlog holes that were left in the masonry of castle walls.

Some medieval hoardings have been reconstructed - including

the Chateau Comptal at Carcassonne.

Hourds were later replaced machicolations, which were an

improvement on hoardings, not least because masonry does not

need to be fire-proofed. Machicolations are also permanent

and siege-ready.

|

|

|

Internal

View of Hourdes at Carcassonne

|

|

|

|

We have a faint reminder of hourds in our modern hourdings - now

used for advertising.

|

Internal

View of Hourdes at Carcassonne

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

post

hole for hourdes at Carcassonne

|

|

|

|

|

| Hourds at Carcassonne |

|

| |

| Internal View of Hourdes at

Carcassonne |

|

| |

| Hourdes at Carcassonne seen

from below |

|

| |

| hourdes at Carcassonne |

|

| |

| hourds |

|

| |

| Hourdes at Carcassonne - viewed from inside |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Machicolations (Machicoulis)

A

machicolation is a floor opening between the supporting corbels

of a battlement, through which stones could be dropped on attackers

at the base of a defensive wall. A machicolated battlement projects

outwards from the supporting wall in order to facilitate this. A

machicolation is a floor opening between the supporting corbels

of a battlement, through which stones could be dropped on attackers

at the base of a defensive wall. A machicolated battlement projects

outwards from the supporting wall in order to facilitate this.

The design was developed in the Middle Ages when the European crusaders

returned from the Holy Land.

The word derives from the Old French word *machecol, mentioned

in Medieval Latin as machecollum and ultimately from Old French

macher 'crush', 'wound' and col 'neck'. The word Machicolate is

recorded in the 18th c. in English, but a verb machicollāre

is attested in Anglo-Latin. A variant of a machicolation, set in

the ceiling of a passage, was known as a murder-hole.

Machicolations were more common in French castles than their English

couterparts, and when used in English castles they were usually

restricted to the gateway as at 13th-century Conwy Castle.

Machicolations were later used for decorative effect with spaces

between the corbels but often without the openings, and subsequently

became a characteristic of the many non-military buildings, for

example, Scottish baronial style, and Gothic Revival architecture

of the 19th and 20th centuries.

Maciolations are in effect stone versions of hourdes. They represent

an additional level of sophistication and expense. Like hourdes

they enabled defenders to shoot at and drop things on their attackers,

while minimising the risk of danger themselves. The great advantages

were

- Machicolations were permanent features. They did not need to

be constructed in anticipation of attack. They were always ready.

- Unlike hourdes, they could not be set on fire

- They were stronger than hourdes and would withstand crossbow

quarrels and even stones hurled by stone throwing siege engines.

- They looked imposing - a psychological benefit against attackers

who had no such defenses

Where the expense was too great for full scale machilations around

a wall, a cheaper alternative was to build them just over weak spots

like doors and gateways. This is the origin of the brattice

- see below.

|

| Macicoulis |

|

| |

| |

|

| |

| |

|

| |

|

|

Abbazia di San Nilo, Grottaferrata, Rome

with extraordinary machicolations

|

|

|

|

|

The Brattice (Bretèche)

a

brettice is a structure projecting from a wall which enables a defender

to fire on attackers while remaining in relative safety. It has

holes in the floor and usually arrow loops or gun ports in the sides.

It is a sort of miniature macicalation, invariably placed to defend

a specific weak point such as a doorway. a

brettice is a structure projecting from a wall which enables a defender

to fire on attackers while remaining in relative safety. It has

holes in the floor and usually arrow loops or gun ports in the sides.

It is a sort of miniature macicalation, invariably placed to defend

a specific weak point such as a doorway.

In apearance brattices can look very like latrines - but latrines

are never placed over doorways!

|

A Brattice at Carcassonne (missing its front

and side walls)

|

|

| |

|

A Brattice at Carcassonne.

|

|

| |

|

A Brattice at Carcassonne - this one is later

than the one above.

It has a gun port at the front rather than an arrow slit.

|

|

|

|

A Brattice at Carcassonne.

Note the adjacent arrow loops

|

|

| |

|

A Brattice at Carcassonne.

Note the adjacent arrow loops

|

|

|

|

|

|

Meutrieres

Meurtrieres are holes designed for defenders to kill attckers.

Projectiles can be thrown or shot at the attackers while the defenders

remain relatively safe.

They can conveniently be divided into two classes: holes in floors

"Murder Holes" (for dropping dangerous substances or shooting

at attackers) and holes in walls, such as arrow loopholes, used

for shooting projectiles. For arrows they are called arrow slits

or arrow loops (archeres) and for guns they are called cannoniers

(canoniers)

|

| The woman who threw the stone

that killed Simon de Montfort at Toulouse |

|

|

|

|

Murder Holes

Attackers would naturally go for a castle's weak points, and the

these weak points generally included entrances. For this reason

entrance gates were heavily reinforced, often provided with extensive

defensive works called barbicans.

Typically the attackers would need to pass a number of obstacles,

and the defenders would try to pick the attackers off as they were

occupied overcoming these obstacles.

|

Typically these obstacles would include steep inclines, ditches

or moats furnished with draw bridges, and port cullises often

a series of purtcullises.

As attackers were finding a way through a door or portcullis

they would be shot at by the defenders. A simple hole in the

floor of the structure over a gateway provided a convenient

way not only to shoot attackers, but also to drop things on

them.

|

|

|

Looking

Up at a Murder Hole

in the Narbonne Gate at Carcassonne

|

|

|

|

Attackers selected the least pleasant possible items to throw on

their enemies. In the popular imagination this was invariably boiling

oil, but there does not appear to be a single documented insatnance

of oil being used. We do however know of boiling water, molten lead,

and even heated sand (all of which could penetrate armour more easily

than other weapons). Other favoured materials included large stones.

| Murder hole in the Cite entrance

of the Chateau Comptal at Carcassonne |

|

| |

|

A Round Murder Hole seen from above

|

|

| |

|

|

Attackers approaching an external gateway

would be faced by a series of obstacles.

A strong wooden gate would be set behind a port cullis.

In this photograph a portculis would drop between the second

and thiird arch.

|

|

| |

|

This is the view looking up. The slot at

the botto is for a port cullis.

The slot at the top is a type of murder hole.

|

|

| |

Inside the room beyond the murder hole, port cullis and door

is another murder hole set into the centre of the vaulted cieling. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

Arrow slits or loop-holes (archeres)

|

An

arrowslit is a thin vertical aperture in a fortification through

which an archer can launch arrows. An

arrowslit is a thin vertical aperture in a fortification through

which an archer can launch arrows.

It is alternatively referred to as an arrow loop, loop hole,

or archere, and sometimes a balistraria.

The interior walls behind an arrow loop are often cut away

at an oblique angle so that the archer has a wide field of

view and field of fire. Arrow slits come in a remarkable variety.

A common form is the cross. The thin vertical aperture permits

the archer large degrees of freedom to vary the elevation

and direction of his bowshot but makes it difficult for attackers

to harm the archer since there is only a small target to aim

at.

Arrow slits can often be found in the curtain walls of medieval

battlements beneath the crenellations.

The

invention of the arrowslit is attributed to Archimedes during

the siege of Syracuse in 214–212 BC. Slits "of

the height of a man and about a palm's width on the outside"

allowed defenders to fire bows and scorpions (an ancient siege

engine) from within the city walls. The

invention of the arrowslit is attributed to Archimedes during

the siege of Syracuse in 214–212 BC. Slits "of

the height of a man and about a palm's width on the outside"

allowed defenders to fire bows and scorpions (an ancient siege

engine) from within the city walls.

Although used in late Greek and Roman defences, arrowslits

were not present in early Norman castles. They are only reintroduced

to military architecture towards the end of the 12th century,

with the castles of Dover and Framlingham in England, and

Richard the Lionheart's Château Gaillard in France.

In these early examples, arrowslits were positioned to protect

sections of the castle wall, rather than all sides of the

castle.

In the 13th century, it became common for arrowslits to be

placed all around a castle's defences.

|

|

|

Arrow

loophols at Carcassonne - outside

|

|

|

|

In its simplest form, an arrowslit was a thin vertical opening,

however the different weapons used by defenders sometimes dictated

the form of arrowslits. Openings for longbowmen were usually tall

and high to allow the user to fire standing up and make use of the

6 ft (1.8 m) bow. Those for crossbowmen were usually lower down

as it was easier for the user to fire whilst kneeling to support

the weight of the weapon.

It

was common for arrowslits to widen to a triangle at the bottom –

called a fishtail – to allow defenders a clearer view of the

base of the wall.] It

was common for arrowslits to widen to a triangle at the bottom –

called a fishtail – to allow defenders a clearer view of the

base of the wall.]

Immediately behind the slit there was a recess called an embrasure;

this allowed a defender to get close to the slit without being too

cramped.

The width of the slit dictate the field of fire, but the field

of vision could be enhanced by the addition of horizontal openings;

they allowed defenders to view the target before it entered range.

Usually, the horizontal slits were level, which created a cross

shape, but less common was to have the slits off-set (called displaced

traverse slots) as in the remains of White Castle in Wales. This

has been characterised as an advance in design as it provided attackers

with a smaller target, however it has also been suggested that it

was to allow the defenders of White Castle to keep attackers in

their sights for longer because of the steep moat surrounding the

castle.

|

Arrow

loophols at Carcassonne - inside

|

|

|

|

|

When an embrasure linked to more than one arrowslit

– in the case of Dover Castle defenders from

three embrasures can shoot through the same arrowslit

– it is called a "multiple arrowslit".

Some arrowslits, such as those at Corfe Castle, had

lockers nearby to store spare arrows and bolts; these

were usually located on the right hand side of the

slit for ease of access and to allow a rapid rate

of fire.

Arrow loops needed to provide cover as a close as

possible to the walls. This is one reason why towers

were used along the defensive walls - they provided

a way to defend the neighbouring walls.

|

Arrow

slits were angled in such a way that they could provide cover

as close as possible to the foot of the wall. Archers could

achieve angles as small as 5° from the vertical. Arrow

slits were angled in such a way that they could provide cover

as close as possible to the foot of the wall. Archers could

achieve angles as small as 5° from the vertical.

|

Arrow

slits were not always regarded with romanic affection. In the nineteenth

century many castles were used at workshops, stores and peasant

accommodation. To keep out the weather holes like arrow slits would

often be blocked up. Arrow

slits were not always regarded with romanic affection. In the nineteenth

century many castles were used at workshops, stores and peasant

accommodation. To keep out the weather holes like arrow slits would

often be blocked up.

On the right is an example from Carcassonne, where the slit has

been filled with Toulouse brick, preserving the outline of the original

hole.

|

Arrow loophols at Carcassonne

External view

|

Arrow loophols at Carcassonne

External view

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

Cannoniers

Arrow

loops needed altering in later times to allow their use by firearms. Arrow

loops needed altering in later times to allow their use by firearms.

Late Medieval and Early Renaissance castles have cannoniers (for

guns) rather than archeres (for arrows).

The hole is just large enough to pass through an arquebus and

the vertical slot for sighting it.

|

|

|

|

Slighting Castles

Often, once a castle was taken, it would be occupied by its new

masters and it would continue its function of holding down a strategically

important area.

Occasionally

this was not done. Perhaps the castle could not be held because

forces were needed elsewhere (as happened during the Cathar Wars),

or because it was untenable with a large hostile population (again

as happened during the Cathar Wars). Perhaps the castle was taken

only for puniutive reasons (as also happened during the Cathar Wars,

Spanish incursions, and during the Hundred Year's Wars). Or perhaps

the strategic importance diminished, as for Carcassonne and her

five sons after the border between France and Spain was moved back

under the Treaty

of the Pyrenees in 1649. Occasionally

this was not done. Perhaps the castle could not be held because

forces were needed elsewhere (as happened during the Cathar Wars),

or because it was untenable with a large hostile population (again

as happened during the Cathar Wars). Perhaps the castle was taken

only for puniutive reasons (as also happened during the Cathar Wars,

Spanish incursions, and during the Hundred Year's Wars). Or perhaps

the strategic importance diminished, as for Carcassonne and her

five sons after the border between France and Spain was moved back

under the Treaty

of the Pyrenees in 1649.

During the English Civil War, Helmsley Castle was besieged by Sir

Thomas Fairfax.. Sir Jordan Crosland held it for the King for three

months before surrendering. Parliament ordered that the castle should

be slighted to prevent its further use and so much of the castle's

walls, gates and the eastern half of the east tower were destroyed

(see right). However the mansion was spared.

In each case there was good reason for destroying the castle before

leaving it and allowing it to be re-occupied. But destroying a castle

is not easy. Generally it was good enough to do just enough damage

to make it not worth while for anyone to repair it. To damage a

castle in this way is to "slight" it. By analogy we talk

about slighting people too - not desroying them but damaging them.

The castle at Beaucaire

was slighted by Richelieu in 1632, and so were the "Five Sons

of Carcassonne",

five Royal castles (Termes,

Aguilar,

Peyrepertuse,

Queribus

and Puilaurens)

strategically placed to defend the old border against Aragon. In

1652 Richelieu ordered the castle at Termes

to be abandoned and slighted. The walls were destroyed by a master

mason from Limoux,

using explosives, between 1653-1654.

Traditionally, a strategy of slighting fortifications was often

adopted in warfare by the side which had the support of the ordinary

population, against an opponent which may have been militarily strong

but did not have popular support, often an alien invader. Examples

of forces who adopted this strategy include the Bruce brothers in

the Scottish Wars of Independence, the Mamelukes in their wars against

the Crusaders, and the Parliamentary side in the English Civil War.

|

| The Slighted Keep of Helmsley Castle |

|

| |

| |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Learn More about Castle Architecture

|

| Bodiam Castle |

|

| |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

![]()

Arrow

loops needed altering in later times to allow their use by firearms.

Arrow

loops needed altering in later times to allow their use by firearms.

Arrow

slits were angled in such a way that they could provide cover

as close as possible to the foot of the wall. Archers could

achieve angles as small as 5° from the vertical.

Arrow

slits were angled in such a way that they could provide cover

as close as possible to the foot of the wall. Archers could

achieve angles as small as 5° from the vertical.